When your parents (or in-laws) come over for the holidays, it may be the first chance you get to practice your grown-up parenting skills. And get a tiny bit of your own back for all those times you heard it as a teenager. “My house, my dog, my rules.” If you’re lucky, you get to practice when you have a dog and not a baby – those discussions are even more fraught.

It came up this week for a training class student of ours. Her mother was coming to visit from overseas. Her mother, who happens to be a fan of a famous dominance-based trainer. And who’s from a culture deeply ingrained with rules, discipline, and pretty much the opposite of reward-based training.

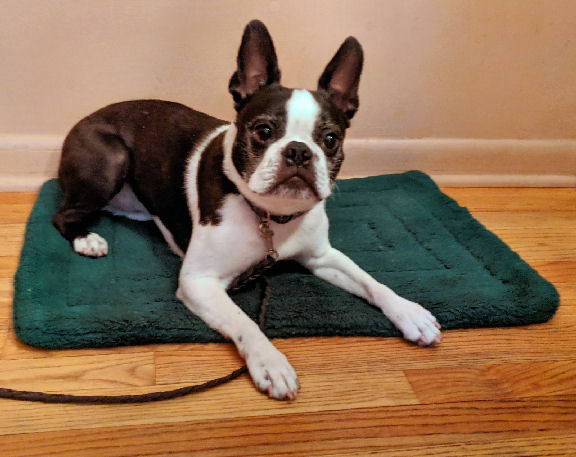

Before Mom arrived, our trainee wanted us to see what was happening with her dog. The pup (seven months old) had been boarded for a few days during Thanksgiving, and had come home with some atypical behaviors.

Not uncommon

Especially for puppies, boarding can be disruptive. The puppy’s schedule is discarded. Depending on the boarding situation, it may be anything from “run with a pack all day,” to stay-in-a-kennel except for yard time. None of the options is inherently bad. There are times when even the most devoted owner just can’t travel with their dog. Boarding is usually a safe option. Ideally, it’s also a comfortable choice and the dog will have some fun with either the staff or other dogs at the facility.

The best way to let your dog absorb the alternative is to practice. Like all things, dogs are adaptable beings if introduced to new things gradually. If your dog goes to a doggy day care that also does boarding, that’s a good place to start. The dog already has a good time during the day. Try to book a single night before a longer stay is necessary. Let the dog see the new routine. And pick them up early the next morning so the dog knows you’re always going to come back.

This dog didn’t get a practice boarding session. After a few days she came home rather insecure and unsettled. She was barking uncharacteristically at people coming into the house. Even at her own family and the family’s familiar baby-sitters.

Back to her comfort zone

So we became the dog’s “cookie people.” That’s a technique straight out of the “Reactive Dog Recipe.” Most reactive dogs are afraid. The objective is to teach them that new people are sources of delicious treats and completely non-threatening. Basically, we walked into the house and threw treats on the floor in front of the dog while we talked to the people. We didn’t look at the pup, we certainly didn’t talk to her. Just calmly had a conversation with her people. In this case, because the dog was just a bit unsettled, not really reactive, and we’re familiar to her, it took less than five minutes for her to calm down.

With Mom arriving two days later, the puppy’s owner now had a plan of action. Leave the pup in her crate until Mom came in, got comfy, and was ready to greet the dog. Remember – your house, your dog, your rules.

Until, of course, Mom came and refused to reward a dog that was barking at her. It looks that way to someone who doesn’t take into account the dog’s emotional state, fear. Barking is actually a low-grade response to fear – our own Tango’s fear-aggression came out in lunging, snarling, and trying to bite. Since Mom wouldn’t get on board, the owners did the treat-tossing. Not ideal, but Mom doesn’t get to decide – not her house, her dog, or her rules.

Familiarity breeds comfort

With this approach, the puppy getting treats every time she saw Mom, the dog was able to relax and accept the new person in just a couple of days. There was no interaction between them until the dog was ready to initiate it. Taken at the puppy’s pace, everything is working out great. They sent us a picture of the puppy relaxing on the couch with Mom today. Everything’s going to be fine. Until Dad arrives tomorrow and we start all over again.